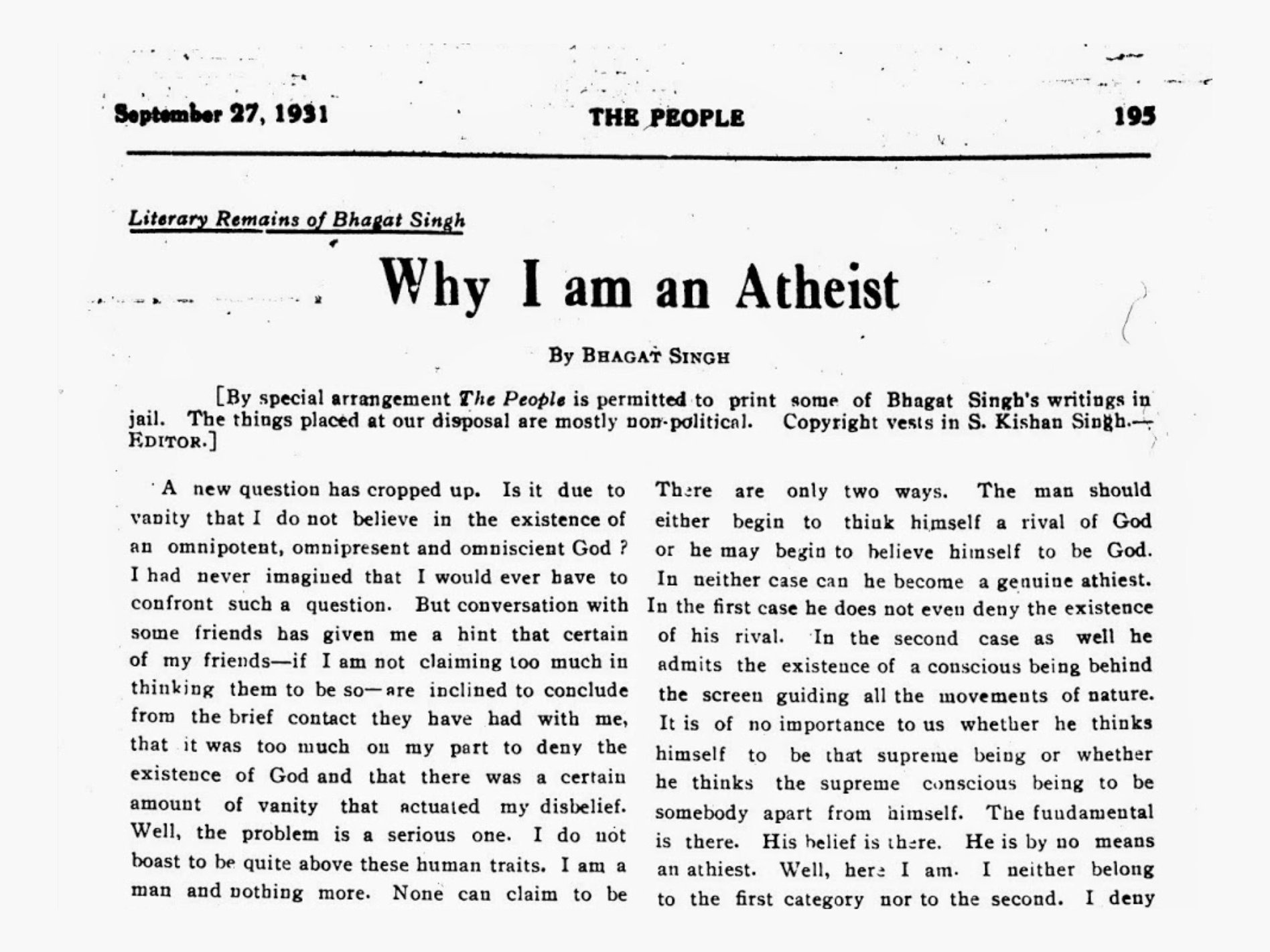

Why I am an atheist: Bhagat Singh's essay

Indian revolutionary Bhagat Singh's essay 'Why I Am an Atheist', written at 23 from jail, challenges blind faith and advocates for reason and critical thinking.

Published on

Here are some of my favourite passages from Bhagat Singh’s essay, which I find noteworthy. The excerpts are listed in the order they appear.

On the importance of critical thinking and the dangers of blind faith

Criticism and independent thinking are the two indispensable qualities of a revolutionary. Because Mahatamaji is great, therefore none should criticise him. Because he has risen above, therefore everything he says —may be in the field of Politics or Religion, Economics or Ethics— is right. Whether you are convinced or not you must say: “Yes, that’s true”. This mentality does not lead towards progress. It is rather too obviously reactionary.

[…] Any man who stands for progress has to criticise, disbelieve and challenge every item of the old faith. Item by item he has to reason out every nook and corner of the prevailing faith. If after considerable reasoning one is led to believe in any theory or philosophy, his faith is welcomed. His reasoning can be mistaken, wrong, misled, and sometimes fallacious. But he is liable to correction because reason is the guiding star of his life. But mere faith and blind faith is dangerous: it dulls the brain and makes a man reactionary. A man who claims to be a realist has to challenge the whole of the ancient faith. If it does not stand the onslaught of reason it crumbles down.

On the Hindu concept of sufferings as a divine punishment for sins committed in the previous life

Poverty is a sin, it is a punishment. I ask you how far would you appreciate a criminologist, a jurist or a legislator who proposes such measures of punishment which shall inevitably force men to commit more offences. Had not your God thought of this, or he also had to learn these things by experience, but at the cost of untold sufferings to be borne by humanity?

On divine inaction

I ask why your omnipotent God does not stop every man when he is committing any sin or offence? He can do it quite easily. Why did he not kill warlords or kill the fury of war in them and thus avoid the catastrophe hurled down on the head of humanity by the Great War? Why does he not just produce a certain sentiment in the mind of the British people to liberate India? Why does he not infuse the altruistic enthusiasm in the hearts of all capitalists to forego their rights of personal possessions of means of production and thus redeem the whole labouring community —nay, the whole human society, from the bondage of capitalism? You want to reason out the practicability of socialist theory; I leave it for your almighty to enforce it. People recognise the merits of socialism in as much as the general welfare is concerned. They oppose it under the pretext of its being impracticable. Let the Almighty step in and arrange everything in an orderly fashion. Now don’t try to advance round about arguments, they are out of order. Let me tell you, British rule is here not because God wills it, but because they possess power and we do not dare to oppose them. Not that it is with the help of God that they are keeping us under their subjection, but it is with the help of guns and rifles, bomb and bullets, police and militia, and our apathy, that they are successfully committing the most deplorable sin against society —the outrageous exploitation of one nation by another. Where is God? What is he doing? Is he enjoying all these woes of human race? A Nero; a Changez!! Down with him!

On the belief in God

If no God existed, how did the people come to believe in him? My answer is clear and brief. As they came to believe in ghosts and evil spirits; the only difference is that belief in God is almost universal and the philosophy well developed. Unlike certain of the radicals I would not attribute its origin to the ingenuity of the exploiters who wanted to keep the people under their subjection by preaching the existence of a supreme being and then claiming an authority and sanction from him for their privileged positions, though I do not differ with them on the essential point that all faiths, religions, creeds and such other institutions became in turn the mere supporters of the tyrannical and exploiting institutions, men and classes. Rebellion against king is always a sin, according to every religion.

As regards the origin of God, my own idea is that having realised the limitation of man, his weaknesses and shortcoming having been taken into consideration, God was brought into imaginary existence to encourage man to face boldly all the trying circumstances, to meet all dangers manfully and to check and restrain his outbursts in prosperity and affluence. God, both will his private laws and parental generosity, was imagined and painted in greater details. He was to serve as a deterrent factor when his fury and private laws were discussed, so that man may not become a danger to society. He was to serve as a father, mother, sister and brother, friend and helper, when his parental qualifications were to be explained. So that when man be in great distress, having been betrayed and deserted by all friends, he may find consolation in the idea that an ever-true friend, was still there to help him, to support him and that he was almighty and could do anything. Really that was useful to the society in the primitive age. The idea of God is helpful to man in distress.

Learn more

The essay can be accessed in its entirety on marxists.org. It was published posthmously on 27 September 1931 in The People.

Attribution

CopyLeft: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license 2.0, by Marxists Internet Archive, 2020, on this document. The text itself is in the public domain.